Back in 2017 I was really interested in emulator development. I read that CHIP-8 was a great introductory system and decided to write my own emulator for it. I was a C programming novice at the time but figured it’d still be a good choice for a project that dealt with a lot of low-level details and mechanics. After a few weeks of work I was able to successfully emulate CHIP-8 games but knew that there were some lingering bugs. Once I cleaned them up and got the finished the project, I moved on and never touched the codebase again. You can find this old version at this commit.

In subsequent years I continued to write more C and hone my overall programming skills. Recently, I walked through this project again and my interim years of experience became clear. Almost every aspect of the code and how it was structured was outdated relative to my modern habits. I knew that a good amount of tender loving care was going to be needed in order to get the project up to my current standards.

Lingering Problems Link to heading

The issues I found upon reviewing this code can be grouped into the following categories:

- Naive Makefile - The Makefile I originally wrote was simple and effective. However, it wasn’t POSIX-compliant and relied on extensions that are specific to GNU Make. This lack of compliance meant that the build was unlikely to work on non-GNU systems such as macOS or BSD variants. In addition to the lack of compatibility, the original Makefile only builds the target binary and nothing else. I’d like to to also build a test binary, a static library, and a shared library.

- Tight Coupling - The original codebase was structured as three tightly-coupled sections:

input.c,graphics.c, andchip8.c. These sections corresponded to keyboard-based input handling, graphical output, and then everything else. There are definitely better ways to break the pieces of an emulator apart than this. Having such large, over-scoped chunks made it difficult to look at specific concepts in isolation. I’d prefer to employ a project structure that more clearly defines the individual ideas of an emulator. - Global State - Each of the three sections mentioned above had global state tied to their translation units. This meant that almost none of the project’s functions were pure or even thread-safe. Even though this emulator doesn’t use threads, I don’t like having the possibility blocked from the start. These quirks also made the sections very difficult to test because every function call would change some global state that affected subsequent calls.

- Lack of Tests - This problem is fairly self-explanatory. The project had no tests at all! This was due to a couple reasons. First, I didn’t know how to write tests into a C project. I didn’t understand Makefiles or libraries enough to add test execution into the build. Second, the global state mentioned previously made it hard to decide what to test. The whole project was this big tangle of code which made any test look daunting.

- Poor Platform Support - Another facet of my inexperience with C and building C projects was the absense of portability. The project was only ever built and ran on Linux. I’ve since learned an effective approach for writing cross-platform C applications and would like to see this emulator working on Linux, macOS, and Windows.

Mighty Makefile Link to heading

The original Makefile had a fairly linear process: use GNU Make extensions to list all of the source files, use a suffix rule to compile C source files into object files, and then link the target binary. Simplified, it looks like this:

SRCS = $(wildcard src/*.c)

HEAD = $(wildcard src/*.h)

OBJS = $(patsubst %.c, %.o, $(SRCS))

skylark: $(OBJS)

$(CC) -o $@ $^ $(LDFLAGS)

%.o: %.c $(HEAD)

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c $< -o $@

This small excerpt alone contains three non-POSIX, GNU Make extentions: wildcard, patsubst, and $^.

Additionally, this Makefile is hard-coded to only build a single target: the main binary.

There is little flexbility for customizing the build in its current form.

What I would prefer is a more free-form, ad hoc mapping between source files and build targets: executable binaries, static libraries, and shared libraries.

Build Goals Link to heading

More specifically, I’d like to be able to build the following targets:

| Target | Dependencies | Description |

|---|---|---|

| libskylark.a | All non-main sources | a static library |

| libskylark.so | All non-main sources | a shared library |

| skylark | libskylark.a, src/main.c | the actual CHIP-8 emulator |

| skylark_tests | libskylark.a, src/main_test.c | a binary that runs the project’s tests |

Fortunately, this situation is exactly what Make was built to solve. This table of build targets can be easily expressed via Make’s simple system of targets, rules, and dependencies.

Restructured Link to heading

Below is a simplified representation of the new Makefile.

# declare library sources

libskylark_sources = src/chip8.c src/inst.c src/op.c

libskylark_objects = $(libskylark_sources:.c=.o)

# express dependencies between object and source files

src/chip8.o: src/chip8.c src/chip8.h src/inst.h

src/inst.o: src/inst.c src/inst.h

src/op.o: src/op.c src/op.h src/inst.h src/chip8.h

# build the static library

libskylark.a: $(libskylark_objects)

$(AR) rcs $@ $(libskylark_objects)

# build the shared library

libskylark.so: $(libskylark_objects)

$(CC) $(LDFLAGS) -shared -o $@ $(libskylark_objects) $(LDLIBS)

# build the main executable

skylark: src/main.c libskylark.a

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) $(LDFLAGS) -o $@ src/main.c libskylark.a $(LDLIBS)

# build the tests executable

skylark_tests_sources = src/chip8_test.c src/inst_test.c src/op_test.c

skylark_tests: $(skylark_tests_sources) src/main_test.c libskylark.a

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -o $@ src/main_test.c libskylark.a

# inference rule for compiling source files to object files

.SUFFIXES: .c .o

.c.o:

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c -o $@ $<

Though longer than the original, this version builds more targets and retains more flexibility. This is the exact “loose mapping” of source files to build targets that I was going for. The libraries depend on the source files, the executables depend on the libraries, and everyone is happy. Additionally, the explicit expression of interdependencies between modules allows Make to optimize the changes and only rebuild what is necessary.

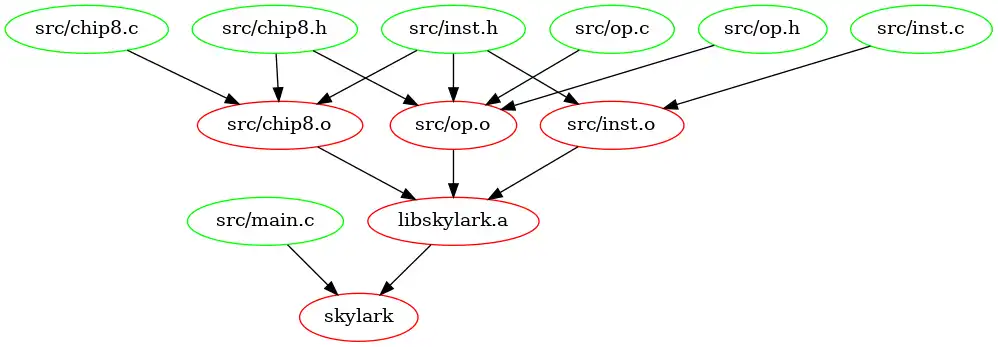

Here is a nice graph of Skylark’s build hierarchy:

Summary Link to heading

That wraps the Makefile revamp! It is definitely a lot more flexible than the old version and does a lot more work. I’m much happier with the way it is written now. You can find the full, current version here:

Functional Foundations Link to heading

Some of the functions in the original version are very “messy” in terms of what they do. In my opinion, a good function should be clear about the data that goes in and the new data that comes out. In addition to this, a good function should have no side-effects. Side-effects make a function more difficult to reason about in isolation and harder to test.

Here is an example of a function from the old version that I’m not satisfied by:

void chip8_emulate_cycle(void);

What on earth does this function do? At a high level, it probably emulates a CHIP-8 cycle, but what does this mean in terms of actual data transformation? Given this definition, it is almost impossible to know. Furthermore, how would you test this function? On the surface, no data goes in and no data comes out. Looking at the implementation, however, we can see that this function does a few things: decode the next instruction and then perform the corresponding operation. How can we make this function more readable and testable?

In my experience, the best way to design a system like this is to map out the different data types and how they transform and interact. Do this both at a conceptual level and also in terms that are specific to your programming language. For the problem of emulating a CHIP-8 cycle, I came up with three important data types:

- instructions encoded as machine code (represented as

uint16_t) - instructions decoded as a map type (represented as

struct instruction) - CHIP-8 internal state (RAM, stack, registers, etc) (represented as

struct chip8)

In terms of these high level data types, the process of emulating a cycle goes as follows:

- Fetch the next machine code instruction

- Decode it into an instruction map type

- Apply the operation to the CHIP-8 state

We can implement these transformations as pure functions:

int instruction_decode(struct instruction* inst, uint16_t code);

int operation_apply(struct chip8* chip8, const struct instruction* inst);

The first function takes an encoded instruction (as a uint16_t) and decodes in into a struct instruction.

The second takes an instruction and applies its operation to the struct chip8.

Note that even though these functions mutate one of their arguments, it doesn’t make them impure.

If all arguments and the data they point to are the same, then the functions result in the same changes.

Effective immutability of these parameters could be achieved by the caller making copies before / after the call.

This strategy might not be referentially transpartent but it is still simple to reason about and test.

Overall, almost every function in a system can be shaped in a way that is closer to purity.

Dealing with I/O (keyboard input, graphical output, etc) is always an exception to this, however.

Due to this, I always leave I/O-based code at the top of the project (as close to main as possible) and don’t let it seep down into the rest of the functional core.

This idea stems from a great talk by Brandon Rhodes called Hoist Your I/O.

In this Python-based presentation, he explains the value of keeping I/O-based and pure functional code separated.

Tactical Testing Link to heading

To be completely honest, most of the C code that I’ve written hasn’t ever been “formally” tested. I would sometimes throw in minimal testing header like minunit but wouldn’t fully utilize it. This lack of testing isn’t a problem when writing in other languages such as Python or Go. For Python I use pytest and for Go I use the builtin testing package. Perhaps it has always been a convenience issue? Or maybe the added build complexity wasn’t worth it to me? Either way, things have changed!

My current approach for testing C programs is extremely minimal. I had a few goals in mind when bringing it all together:

- keep it simple (with little overhead to the project)

- keep it modular (such that each section of the code has its own tests)

- keep it data-driven (with lists of test data and expected outcomes)

All of these goals come from how pleasant of an experience it was to write tests within a Go project.

I don’t really have a need for before and after hooks.

I have no need for mocks.

I want a straightfoward way to validate some behavior and return true or false.

Overall, I want something that adds value to the project: not something that bogs it down.

Here is the gist of it:

- Each test function adheres to a standard interface

- The tests for a given module are placed in

<module>_test.c - All of the tests are collected, executed, and counted in

main_test.c - The

main_test.cfile gets compiled intoskylark_tests - When executed,

skylark_testsreports the results and exits accordingly

The data-driven aspect of the individual tests comes mostly from C99’s designated initializers.

By using an an array of literal structs I can enumerate pairs of test inputs and their expected outputs.

These pairs are then looped over and if anything doesn’t line up, we print an error and return false.

Otherwise, the test passes and returns true.

You can see an example of this being applied to instruction decoding in instruction_test.c.

In a similar fasion, all of the tests are collected and iterated over in main_test.c as an array of:

typedef bool (*test_func)(void);

This approach is clean and simple but it does have some downsides. For one, the error messages contain no test idenfitication by default. This means that all error message must be extra verbose and include what is being tested. There might be a way to make this cleaner with some macros but thus far I’ve not found a system that works well and is worth the added complexity. I strictly want just enough testing power to verify a function’s behavior, lock it in place, and move on.

Plentiful Platforms Link to heading

The original version of Skylark was limited to Linux mainly because I didn’t know how to achieve anything else. However, cross-platform C programs are now something that I can confidently build. Most of this progress is thanks for Chris Wellons and his amazing blog. He has written many posts about writing portable C. I even wrote a post of my own about this! It describes how to write and build cross-platform, multimedia applications using SDL2 and OpenGL.

In short, the process is as follows:

- Each platform has its own Makefile

- Unix-like systems build the project natively

- Windows builds are cross-compiled (using mingw-w64) from a Unix-like system

The Makefiles themselves are structured similarly.

The Linux (Makefile) and macOS (Makefile.macos) Makefiles are nearly identical.

They occasionally vary in terms of some library names, include directories, and linker flags.

The Windows Makefile (Makefile.mingw) is different in a few notable ways:

- Shared libraries have the extension

.dllinstead of.so - Executables have the extension

.exe - Dependencies are downloaded as pre-built libraries

When it comes to dependencies, the approach differs depending on the platform. The Linux and macOS builds expect libraries to be installed prior to building (SDL2, in this case). For Windows, however, it is simpler to download the pre-built libraries at build time and statically link them into the target binary.

This method for handling libraries for Windows builds is very simple and effective.

By linking them in statically, the resulting .exe is able to be distributed with zero extra dependencies.

Just build, distribute, and run!

It is a great solution to a potentially very messy problem.

Conclusion Link to heading

There we go! My CHIP-8 emulator is now completely revamped and modernized. I’ve thrown all of my newfound experience at it and made it shine. I hope that this journey has been interesting and that you picked up a useful trick or two. Thanks again for reading and I’ll see you next time!